By Michael Chotiner

My friend, an architect and builder in the Washington, D.C., area, recently told me an interesting (if not disturbing) story about a job he worked on. He’d been asked to carry out repairs on a four-story building with shops on the ground floor and apartments above that had been damaged by an improperly installed fire sprinkler system.

In the course of surveying the site to learn what it would take to put things back in order, Jeremy found that there was no emergency lighting on the top floor of the building, and there never had been. The owners weren’t happy about the thousands they’d be assessed to pay for correcting the illegal conditions, but in cases like this, the buck stops with the owners.

It’s hard for me to understand how the fault in the emergency lighting system wasn’t caught sooner. A number of national building standards organizations and the federal government have established requirements for emergency planning, and local building code and fire officials have authority to enforce the rules.

Who Needs an Emergency Plan?

All commercial buildings and multi-family residences are required to establish evacuation procedures to ensure that occupants can get out in a safe, orderly manner under emergency conditions. The rules aim at a broad range of emergency scenarios, including:

- Fires

- Floods

- Earthquakes

- Dangerous weather conditions

- Gas leaks

- Contamination by hazardous substances

- Power failures

Emergency Plan Basics

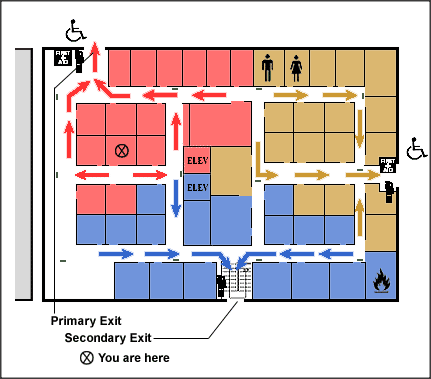

The first step in creating an emergency plan is to determine safe, efficient routes for building occupants to evacuate a building when necessary. The floor plan above was developed by OSHA to provide examples of best practices.

- Designate primary and secondary exits.

- Plan the most efficient routes to the various exits for occupants in each area of the building to avoid over-congestion of any single exit.

- Identify wheelchair-accessible exits.

- Direct building occupants away from elevators and storerooms containing hazardous materials and/or equipment.

- Identify emergency exits and routes to exits with signs.

Emergency Lighting for Egress Routes

Planning standards require provisions for lighting egress routes designated for emergency evacuation. For that reason, lighted exit signs and other types of emergency lighting fixtures must be installed along established evacuation paths. Some of the fundamental rules from the model codes are paraphrased below:

- Emergency lighting must be arranged to provide illumination along the path of egress.

- Exits must be marked by approved signs that are readily visible from any direction of exit access. Every sign must be suitably illuminated by a reliable light source. Externally and internally illuminated signs must be visible in both the normal and emergency lighting mode.

- An exit sign with a directional indicator must be placed in every location where the direction of travel to reach the nearest exit is not apparent.

- Any door, passage or stairway that is neither an exit nor a way of exit access (and that is so located or arranged that it is likely to be mistaken for an exit) should be identified by a sign reading “NO EXIT.”

Under most local building and fire codes in force today, emergency fixtures equipped with rechargeable batteries satisfy emergency planning standards. The batteries store energy supplied by the building’s primary electrical system and use it to power lights during a power failure. In most cases, emergency fixtures must have the capacity to store at least enough electricity to power lights for up to 90 minutes.

Emergency Plan Follow-Up

Simply having an emergency plan isn’t enough. Most applicable codes require emergency plans to be formalized in writing, distributed to building occupants, reinforced with posters illustrating the floor plan and escape routes, and rehearsed through periodic evacuation drills. Plans must be updated when changes occur — like remodeling that alters floor plans, changes in staffing and the like.

Most local codes require emergency lighting systems to be tested for at least 30 seconds once a month and for a full 90 minutes at least once a year. Building operators are required to keep a log of the test dates and results.

That’s why I was surprised when Jeremy told me about the missing emergency lights in the building he was working on. Anybody paying attention to the prescribed procedures should have discovered the issue long before Jeremy did.

To be sure, regulations prescribing emergency planning are complex — and they vary in specifics from state to state and city to city. Codes related to emergency systems are sufficiently technical that they should be designed and implemented by professionals who are familiar with local best practices.

But building owners and business operators shouldn’t defer responsibility for emergency systems entirely to the pros or implement them just because they’re required by law. If you don’t make a plan or monitor its effectiveness, just like the co-op owners in Jeremy’s defective building, you’ll eventually have to pay, one way or another.